‘I’m afraid now. I believe it could happen here’ – do white supremacists pose a threat in Ireland?

Originally published by the Irish Independent on August 10, 2019

The ‘Great Replacement’ conspiracy theory seems to have inspired the mass shooter in El Paso – and is widely circulated in Ireland. After attacks on mosques and Direct Provision centres, do white supremacists pose a threat here? Kim Bielenberg reports

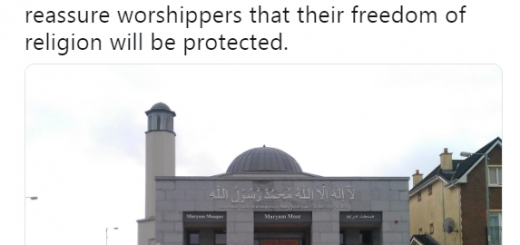

Ibrahim Noonan knows what it is like to be the victim of a hate crime perpetrated by far-right extremists. The Imam of the Maryam Mosque in Galway city told Review he was telephoned by an anonymous caller who warned him that his mosque would be targeted. The caller also informed Noonan that he himself would be attacked.

The anonymous right-wing activist said he didn’t like Muslims, and didn’t want mosques and mass migration coming into Ireland

Twelve days ago, in the middle of the night, the Maryam Mosque was duly attacked and vandalised, leaving a community of Ahmadi Muslims concerned for their safety. Windows were smashed, and the imam’s office trashed, with family photos destroyed and the mosque’s tricolour thrown on the ground.

History has shown us that a descent into barbarism can begin with attacks on mosques, churches and synagogues – and can end up with assaults, murder and the kind of mass shootings we have just seen in the US.

The Galway mosque incident came after recent arson attacks on planned asylum seeker centres in Roosky on the Leitrim/Roscommon border and Moville in Donegal.

Ibrahim Noonan told Review this week: “I am concerned that this is getting to another level in Ireland – maybe next time there will be a petrol bomb, or a physical attack.”

Ireland is fortunate to have escaped the mass shootings that have become commonplace in America, and frequently linked to white supremacist ideology.

The bloodiest mass shooting of last weekend in the United States was allegedly carried out by a suspect, Patrick Crusius, who had just posted a racist manifesto on the internet message board 8chan.

Some of the messages conveyed by the alleged killer of 22 people would have been familiar to those who have followed the increasingly vocal far-right groups operating in Ireland.

In recent months – on YouTube channels, on Twitter and more shadowy enclaves of the internet – they have warned of a plan for a “great replacement” of the indigenous Irish people by foreigners.

They claim that mass migration, particularly from Africa and the Middle East, will render white populations extinct in countries such as Ireland.

Before his rampage in the Walmart store in El Paso, Crusius posted a manifesto sympathising with the white supremacist who perpetrated a mass shooting in Christchurch, New Zealand, earlier this year.

He said his actions were “a response to the Hispanic invasion of Texas”, words that chillingly echoed the racist rhetoric of Donald Trump, who has also frequently warned of an “invasion” at the Mexican border.

Crusius claimed in his 2,300-word document: “I am simply defending my country from cultural and ethnic replacement brought on by an invasion.”

Over the past year, talk of a conspiracy to replace the Irish people with migrants has circulated widely on the internet in various forms. It is a portable conspiracy theory that can be transplanted into any country.

Mainstream social media

Professor Maura Conway, a Dublin City University authority on extremist internet networks, says: “The Great Replacement theory is not confined to right-wing extremist circles and the dark recesses of the internet. It is now very widespread on mainstream social media platforms as well.”

These sentiments are expressed on numerous Irish right-wing YouTube channels. Sometimes the message is insidious, rather than overt, with the focus on the threat to our culture and heritage from newcomers, rather than on race.

The man said to be behind the influential conspiracy theory is the French writer Renaud Camus, author of The Great Replacement.

“The great replacement is very simple,” Camus has explained in an interview. “You have one people, and in the space of a generation you have a different people.”

According to the Camus ideology, which first referred to France, the indigenous people are replaced by non-white peoples – mainly from Africa or the Middle East.

He said in one interview: “A people was here, stable, had been occupying the same territory for 15 or 20 centuries. And suddenly, very quickly, in one or two generations, one or several other peoples substitute themselves for him. He is replaced, it is not him anymore.”

Far-right groups have seized on these ideas, pushing the notion that native populations across America and Europe are being deliberately wiped out by shadowy political and corporate forces, stripping a country of its ancestral heritage in the process.

According to the writer Rosa Schwartzburg, one of the reasons why the “great replacement” theory was able to take hold so firmly in the US was because of the country’s history of earlier white replacement conspiracies.

It has become mixed up with another theory that has been around for well over a century – the “white genocide” conspiracy.

According to Schwartzburg, this came about after the abolition of slavery and constituted a belief that the US was on the brink of a “race war”, in which freed slaves would rise up and kill their former masters. This belief has recurred over the past century.

In some versions of the replacement theory, Jews are blamed for the planned obliteration of the white population either directly, or implicitly using “dog whistle” terms such as “globalists” to refer to them.

When neo-Nazis marched at Charlottesville in 2017 in a torchlit procession, they chanted: “Jews will not replace us!” – a direct reference to the ideology that has helped to inspire the recent spate of mass shootings.

In Ireland, we may like to think that we are immune to the kind of attacks that happen in America with alarming frequency.

In the US, in the era of Donald Trump, white nationalist bigotry has gone mainstream and those with violent inclinations have easy access to guns.

Christchurch attacks

By contrast, parties with extreme right-wing views have not fared well in elections in Ireland – and it is much harder to get your hands on an assault rifle. But if Ireland thinks that it can stand apart and be complacent, the attack on Christchurch in New Zealand, where 51 people were killed, was a wake-up call. Professor Arie Perliger, director of Security Studies at the University of Massachusetts, says the white supremacist movement is international.

“These conspiracy theories are spreading very quickly and achieving transnational attention. Because of the internet, no country is isolated any more, apart perhaps from North Korea. Most Western countries are facing these challenges.”

Shane O’Curry of the European Network Against Racism Ireland (Enar) said he had seen a rise in extreme right-wing activity online in recent months.

“A lot of the language used has migrated from extremist sites to moderate platforms. It creates a climate in which someone inclined to violent action will feel that they have permission to act on behalf of the majority.”

O’Curry was particularly disturbed by the attacks on planned Direct Provision centres in Moville and Roosky between last November and January. “Both of these attacks happened in a short space of time, and I have no doubt that online rhetoric provided a context for it.

“These attacks and the incident at the mosque in Galway show that people are prepared to take it further. This could tip over into something a lot more horrific and sinister.”

O’Curry claims that gardaí don’t have the capacity to respond to hate crimes in a way that recognises them as hate crimes, and there are only a tiny number of convictions for incitement.

It is hard to gauge precisely if there has been an increase in hate crimes in recent years. Supt Dave McInerney, former head of Garda Racial, Intercultural and Diversity Office (GRIDO), said there had been no dramatic upsurge, given the rise in the immigrant population.

Niamh Kirk, a media analyst at DCU who has monitored far-right activity online, said there had been upsurge in extremist activity in terms of the number of online accounts that are active in Ireland.

“Because they are anonymous and transnational, it is hard to tell if there is an increase in the number of people involved. But there is certainly an increase in the number of accounts.

“There are now thousands of far-right Twitter users, and YouTube also has a large presence with around 50 channels.”

Kirk has not come across Irish activity on 8chan, the message board now notorious for the posts by mass shooters, including the alleged El Paso killer.

But another popular internet message board, 4chan has a strong Irish right-wing presence, and is a cesspool of vulgar racist, anti-semitic and violent homophobic abuse.

One of the milder posts has a picture of Leo Varadkar with the message: “This is what our ancestors fought for. A homosexual Indian man.”

Another derogatory post about an Irish politician is a clear case of incitement, including the remark: “She deserves a bullet.”

One of the difficulties in dealing with hate speech of this type is that many of the websites where hateful posts are published originate in the US.

After 9/11, and the sheer scale of the attack on the Twin Towers, the focus of US law enforcement was on tackling Islamist extremism.

Draconian new laws were passed to avert the terrorist threat from groups such as Al Qaeda, and later on from Isil.

But Professor Arie Perliger says the US authorities were much slower to react to domestic terrorism, which is mostly perpetrated by white supremacists.

“That has become a much bigger threat in recent years, but when I raised the issue in 2012, people were sceptical and there was even a backlash against me,” says Perliger.

Professor Maura Conway says the borderless nature of the internet makes it difficult to police when it comes to hate speech.

“Most of the social media companies come from the United States and there is a very different attitude to free speech in the US and the EU. In the United States, they have tended to have a laissez-faire attitude.”

Cracking down on domestic terrorism will require resolve from the authorities, and will test the limits of American free speech. As a New York Times commentary put it this week: “Espousing hate-filled, white-supremacist, anti-immigrant views is protected under the US Constitution. So is buying guns.”

Shutting down propaganda

Even virulent racist groups like the Ku Klux Klan are legal. Conway says the authorities in the US and Europe were successful in shutting down propaganda emanating from Isil.

“The big difference is that Isil is an organisation, but right-wing extremism is an ideology. So, you are comparing apples and oranges.”

Because Isil propaganda was branded, social media platforms were able to use technology to track it and take it down.

“You can’t do the same thing with right-wing extremism, because there isn’t a single or dominant organisation or group.”

The Irish white supremacists who parrot ideology copied and pasted from extremists in the US may lay claim to preserving our heritage. But in fact they endanger decent community values cherished by Irish people, no matter what colour or creed.

At the Galway mosque, something has been lost – a sense of peace and security. Ibrahim Noonan hoped that the mosque could be an open place for all-comers, but now he has to put up fences.

“We have to turn it into a fortress, something I never wanted to do,” he says. “I have to look outside my door twice to check who is there in case someone is following me.”

Referring to the mass shootings that are a stain on American life and recently brought tragedy to Christchurch, the Imam says: “I’m afraid now I believe it could happen here in Ireland. All it takes is just one guy to put it into his head that he needs to go and do it.”